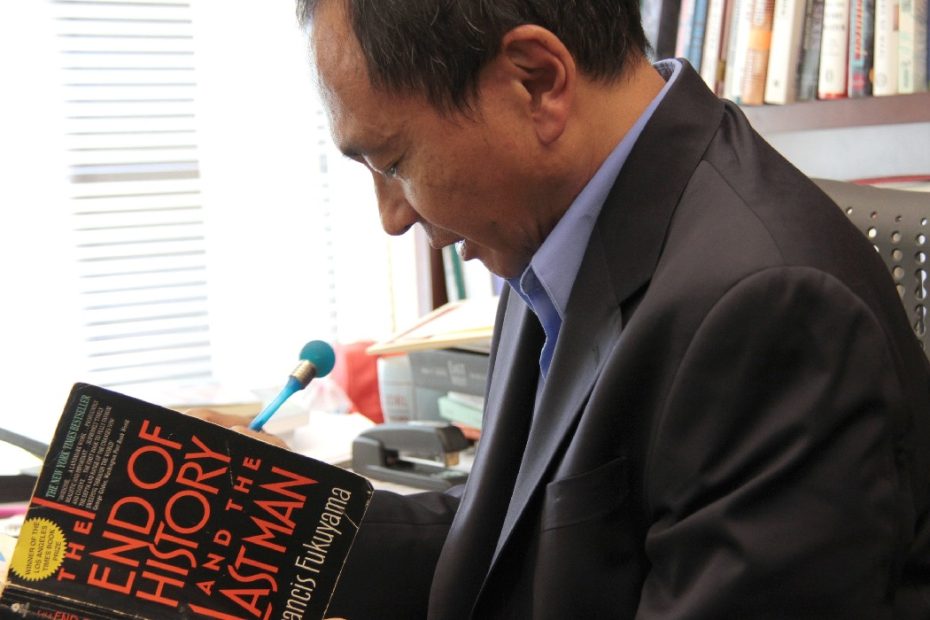

Few books have a fate as “bumpy” as Fukuyama’s “The End of History and the Last Man”. Since its publication in 1992, it has traversed countless applause and just as many rotten eggs. The brutal political atmosphere has gradually turned a book of reasoning into an ideological symbol. Twenty years have passed, and it may be necessary to revisit this book, reflect on the rights and wrongs of this book with the changes of the times in the past 20 years, and also use this book as a coordinate to analyze the trend of the times.

Undoubtedly, the enthusiastic embrace or critique of “The End of History” stems from its explosive core conclusion that history will end in liberal democracy, and Bourgeois in liberal democracy will be “the last man”.

How can history end with “liberal democracy” originating from the West? Looking at it, in the past 20 years, there have been “labor pains” of transformation in Eastern Europe; There is the regression of democracy in countries such as Russia and Venezuela; There is the rise of religious extremism in many regions; There are United States failures to “transplant” democracy to Afghanistan Iraq; There is the rise of the “China model”; Not to mention the various “democratic” chaos that we see today in the Middle East, Thailand, Ukraine, and elsewhere…… If the victory of the West in the Cold War meant the “end of history”, then why did history have such ups and downs after the “end”? If the bourgeois in the developed countries of the West is the “last man”, then why are there religious extremists like Osama ·bin Laden, “anti-Western strongmen” like Chávez, and Hutu people who massacre the Tutsi after this “last man”?

These criticisms certainly have their merits. Obviously, the victory in the Cold War did not “Westernize” the whole world overnight. Whether it is the revival of religious extremist forces, the rise of “anti-neoliberal” discourse, or the rise of “other paths” such as the “China model”, the “Russia model”, and the “Venezuela model”, all show an effort to “break through” ideology. However, there seems to be a problem with the criticism of the book based on these phenomena: it is not so much the book itself that they criticize as the title of the book. Perhaps because most critics have not read the book itself, but only its title.

The End of History and the Last Man is a treatise, not a manifesto. Perhaps the fairer and more rewarding thing is to enter the book’s inner rationale and build on it, rather than relying on the ideological label it is attached to and comment on it.

If you read this book carefully, you will realize that when we criticize Fukuyama with the current “chaos of democracies” and “the resilience of authoritarian states”, we are based on a misunderstanding of the book. In fact, even twenty years ago, Fukuyama never denied that these phenomena would persist beyond the “end of history.” In many places in the book, he accurately predicts the long-term nature of such phenomena, such as that “the current crisis of authoritarianism does not necessarily lead to the emergence of liberal democracies, and the emerging democracies are not all safe and stable.” The emerging democracies of Eastern Europe are undergoing painful economic transitions, while the emerging democracies of Latin America are suffering from the terrible legacy of economic chaos. Many of the fastest-growing countries in East Asia, although they have liberalized economically, have not accepted the challenge of political liberalization. In a region like the Middle East, the liberal revolution has not yet spilled over. It is entirely possible for countries like Peru or the Philippines to revert to dictatorship under pressure from serious problems. In other words, whether it is the pain of transition, the regression of democracy, the constraints of history and economics on democratization, or the temptation of “authoritarian growth,” Fukuyama has never denied the assertion that “history is over.”

The problem is that “the triumph we are seeing is not so much liberal practice as liberal idealism”. In other words, as a universal principle of political legitimacy, there was no significant alternative to the idea of liberal democracy after the end of the Cold War. Yes, there are still uneven ideologies in the world today, as evidenced by the rise of the “China model”, for example. However, even the defenders of the “China model” today are mostly trying to argue that the “China model” is suitable for China’s special “national conditions”, rather than arguing it as a “universal principle of legitimacy”, and not many people will enthusiastically export the “China model” to the world like the “export revolution” in the past.

Similarly, we do see all kinds of dictators today, but even dictators recognize the legitimacy of “liberal democracy” as a political discourse, judging by the fact that these dictators either adorn their dictatorship with a “democratic cloak” or justify their dictatorship with a “state of emergency” or “exceptional circumstances.” Otherwise, why should even the most famous authoritarian rulers in the contemporary world – Saddam, Milosevic, Mugabe, and so on – wear the cloak of “elections”? In an era and in a country where the legitimacy of “liberal democracy” was not yet widespread, there was no need for autocrats to do so – Zhu Yuanzhang or Qianlong, for example, never felt that in order to win the hearts and minds of the people, they needed to hold even sham elections. Similarly, even military junta that came to power today through a coup d’état often promise to hold elections – as recently as the military authorities that impose military control over Thailand announced that they would allow elections in a year’s time.

Even though liberal democracy as a universal political idea does establish legitimacy in most regions, how do we know that it is not a temporary phenomenon? Isn’t this “victory” a flash in the pan in the cyclical cycle of history? In what sense can we say that it “ended” history?

This brings us to the core of the book. Fukuyama points out, or rather stands in the Hegelian tradition, that history is fundamentally driven by the need for “recognition”—not just the need for survival or profit—that is the fundamental attribute that distinguishes man from animals. The various institutions in history (slavery, monarchy, aristocracy, communism, fascism, etc.) contain flaws in the “forms of recognition” that constitute the “contradictions” that drive the evolution of history and lead to the renewal of the system. Only liberal democracy satisfies humanity’s need for “recognition” on an equal, mutual, and meaningful basis, so it leads to a relatively stable social equilibrium – in the sense that it constitutes the end of history.

It can be seen that Fukuyama’s argument is not in the sociological sense, but in the psychological sense. He is not defending liberal democracy from the point of view of its “social function”. While he points to the empirical relevance of liberal democracies to economic and social development, he makes it clear that he does not intend to base his arguments for liberal democracies because of the volatile and cyclical nature of this correlation. In fact, he argues, liberal democracy may not be the best choice if people are concerned only with “economic” indicators that satisfy desire and reason: “If people only have desire and reason, they will be content with market-oriented authoritarian states, such as Franco’s Spain, and military rule in Korea or Brazil.” However, they have a passionate pride in their self-worth, and it is this passionate pride that drives them to aspire to democracy, which treats them like adults rather than children and recognizes their autonomy as free individuals. ”

That is, in order to find a measure of the “stability” of the system, if the word “good or bad” is too harsh, he must appeal to a supra-historical criterion rather than a sociological criterion such as “economic development” and “social stability”. This criterion, in his view, is the universal psychological need of human nature to seek “recognition”. Today, we are accustomed to understanding human nature only in terms of the concept of “rational man”, but Fukuyama, with the help of Plato, pointed out that the human soul has three parts: desire, reason, and passion. The universally popular view of human nature of “homo economicus” ignores the part of man who seeks “passion”. Whether it is the war waged by the ancient royal family or the hard work of modern people, it cannot be explained simply by “rational people” – in addition to the pursuit of profit, but also in the pursuit of glory – that is, “recognition”.

It is true that before liberal democracies gained universal legitimacy, recognition was sought through other political systems. Whether slavery, monarchy, or aristocracy, its creation and maintenance are the result of the pursuit of recognition by some. But the problem is that “recognition” under a strict hierarchy is not satisfying. First of all, it is not mutual—the recognition of slave owners to slaves, monarchs to subjects, and nobles to serfs is far less than the recognition of serfs in the opposite direction, and this imbalance constitutes a “social contradiction” that drives the evolution of the system. Secondly, even the recognition of slaves to slave owners, subjects to monarchs, and serfs to nobles is not satisfying because it is based on coercion and dependence. The “love” under the threat of force or the purchase of benefits is not as sweet as the “love” on the basis of spontaneity – only when the other party is a free person with the ability to make ethical choices, can its “recognition” really bring us pleasure and satisfaction. This is in line with our experience – a beautiful girl who is truly in love with a man “this person”, not coerced by him with a gun or bribed with money, her love is truly satisfying to this man; The “recognition” that the teacher receives is truly satisfying if all students choose to stay in a teacher’s class and concentrate on the lesson, rather than because the teacher calls a roll call and the teacher may give a low grade. It is in this sense that not only the weak of a society, but also the strong of a society, need to be “recognized” in the most meaningful way through the social form of liberal democracy—only by giving others freedom and rights can the strong receive meaningful recognition from them.

It is in this sense that it can even be said that history does not end with the end of the Cold War, but after the revolutions in France and the United States – when the “principle of popular sovereignty” was established through war. In fact, after the Battle of Jena in 1806, Hegel declared “the end of history”. What he meant, of course, was not to say that there would be no wars between nations or competition between systems in the history that followed, but that universal and reciprocal forms of human recognition had been found and began to spread by force. The history since then is, in a sense, the history of the spread of liberal democracy. Even the communist system, which appears to be an opponent of liberal democracy, is more of a variant of it—a derivative of different institutions under the same “principle of popular sovereignty.” Fascism, on the other hand, is more of a temporary “atavism” in the evolution of the system – after all, even historical progressives do not assume that this progress will necessarily advance in a linear fashion.

Even if we take “recognition” as a measure of political equilibrium, institutionalizing “recognition” on an equal, mutual, and meaningful basis, does liberal democracy really do it?

If the rise of nationalism and religious extremism, as well as the setback of democratization in developing countries, represent a challenge from the “historical world” to the “post-historical world”, Fukuyama is more concerned or worried about not this, but the contradictions within the “post-historical world.” It seems that in his eyes, the challenge of the “historical world” to the “post-historical world” does not pose a fundamental threat to liberal democracy, because the absolute superiority of the military, economy, science and technology, and even cultural industry of the “post-historical world” is not only sufficient to withstand such a challenge, but is also very likely, as the history of the past two hundred years has shown, to conquer the “historical world” through a process that may be long and tortuous, but eventually penetrates and expands. There is reason not to believe that nationalism, racism, and even religious extremism will fade, but Fukuyama points out that hundreds of years ago, people in the Western world did not believe that the fanaticism and wars caused by Christianity could gradually fade out of the political arena. “Tolerance” and “rationality” can be learned, and in an era of globalization, this learned process will progress even faster than in history – although it is still a long process.

What Fukuyama is really serious about is the contradiction within the “post-historical world”: whether liberal democracy can really bring about equal, reciprocal and meaningful “recognition”. If not, then liberal democracies are far more likely to decay by “implosion” than to be destroyed by the “historical world.” In fact, there are two angles of skepticism.

The first is the leftist perspective. Yes, “equal recognition” brings dignity satisfaction, but people are not equal in a free economy. Whether it is the obvious gap between the rich and the poor in the world today, or even the widening of the income gap within the developed countries, it is an undeniable reality, otherwise the slogans of “anti-neoliberalism” around the world would not have been so marketable, and the Occupy Wall Street movement in all its forms would not have swept the world. Fukuyama’s response to this is an attempt to distinguish between “problems” and “contradictions.” Yes, liberal democracies have many “problems” (including inequality), but these “problems” do not constitute fundamental “contradictions.” The reason why it does not constitute a fundamental contradiction is that liberal democracy, as a mechanism with internal error correction function, is able to solve these “problems” within the system without resorting to institutional replacement itself. For example, the rise of welfare institutions in the twentieth century is a manifestation of the self-regulating capacity of liberal democracy. In contrast, other political systems lack such flexible room for self-adjustment due to the flaws in their power structures, which is why they have decayed one by one.

Now, 20 years later, when we see the preoccupation of Europe and the United States over deficits, the surging leftist movements and protests, and the embarrassingly low approval ratings of heads of government, we wonder if Fukuyama is underestimating the energy of the leftist challenge. It has been said that democracy is “an arms race for good policies” – yes, political competition stimulates the ability of liberal democracies to innovate in policy, but “it is difficult for a good woman to cook without rice”. When people demand high welfare without allowing the government to raise taxes, unable to tolerate inflation, and demanding that the government stimulate the economy, the concept of “rights” is extended indefinitely…… The question of whether this “arms race of policies” will touch the boundaries of a “self-regulating capability” has become a question.

But what troubled Fukuyama more at the time was not the left’s questioning of the “politics of recognition,” but the right’s questioning of it. The typical right would argue that, yes, liberal democracy brings “equal recognition,” but “equal recognition” is unreasonable. In a world where everyone is unequal in ability, wisdom, and virtue, why should everyone be “recognized” equally? Here, Fukuyama quotes Nietzsche extensively, because, in Nietzsche’s view, liberal democracies represent the absolute triumph of the “slaves”. When we decouple “recognition” from “achievement”, “equal recognition” becomes a cloak of value relativism – if an unenterprising person who sits on the couch all day watching TV and eating potato chips can also justifiably demand “equal recognition” from society, then what is the value of such “recognition”?

Just as Fukuyama may have underestimated the challenge of the left to liberal democracy, here he seems to be overestimating the challenge of the right. If Nietzsche, Alexis de Tocqueville and others were forgivable for their pessimism about “liberal democracy” as “the triumph of slaves or the masses” at the beginning of the rise of democracy, it would be arrogant to continue to share the same pessimism today, as the system and its consequences become clear. In fact, at least in terms of the past 200 years of history – although we may not be able to guarantee that this will continue to be the case in the future, the social impulse of “elitism” and the creativity it brings has not disappeared, and it can even be said that it has expanded beyond history: whether it is a business elite like Steve Jobs, a sports elite like Jordan, or a literary elite like Hemingway, whether it is a sophisticated technology like a personal computer, or a superb medical technology like heart bypass surgery, or human exploration of the moon or even Mars, All show that liberal democracies do not necessarily stifle human creativity, courage and skill, but only replace the mechanical elitism that used to be determined by birth, with the organic elitism that is now more associated with ability. In modern liberal democracies, “an unenterprising man who sits on the couch and watches TV and eats potato chips all day” does not receive the same “recognition” as that of Steve Jobs, Jordan, or Hemingway, which is much greater in terms of income and social prestige. So far, at least, the victory of liberal democracy has not meant “the victory of slaves,” as Nietzsche put it. It accommodates, at least to a considerable extent, the differential pattern of recognition – the recognition of wisdom over mediocrity, the recognition of industriousness rather than laziness, and the recognition of courage rather than weakness.

Perhaps the secret of liberal democracy lies precisely in the fact that it contains both “freedom” and “democracy”. Fukuyama and even Nietzsche were pessimistic perhaps because the democracy they saw could only be “illiberal democracy”. The left loaths the inequalities driven by “freedom,” while the right loathes the equal rights demanded by “democracy.” If a system has only “freedom”, sooner or later it may implode from people’s desire for “equality”; If a system is only “democratic”, then it may also quickly be exhausted by the “tyranny of the majority”. But a system that includes both “freedom” and “democracy” has gained vitality precisely because of its inherent tension. The combination is dynamic – taxes can be raised today to boost welfare, taxes can be cut tomorrow to increase dynamism, and diverse – in Europe, the United States, and Japan, democracy and freedom are not combined in the same way. As long as this dynamism and diversity persists, liberal democracies remain fairly flexible and adaptable. If liberal democracies fall into a systemic crisis one day, it is probably because the dynamic balance between freedom and democracy has been upset by the absolute preponderance of one side.

In addition to the skepticism of the left and the right, there is also a dissatisfaction with liberal democracy, which may be called a “nameless” dissatisfaction. This discontent is so inappropriately proportioned to real problems that it is difficult to say what specific social problems are causing it, and it is even the lack of real major problems in the “post-historical world” that leads to this discontent. Fukuyama’s book mentions two situations, one is the belligerence of many people in Germany before the outbreak of World War I; One was the student movement in France in the sixties. In both cases, whether it is “Germany marchers who demand war” or “France students who are fed all day long but hold up Mao’s quotations”, they are not so much troubled by a specific social problem as by the emptiness and boredom of continued peace and prosperity.

In this sense, even if history has reached the “end”, there may be a part of human nature that eternally aspires to be part of “history”, not the bourgeois-like “last man” after the “end” of history. “History” means contradiction, contradiction means conflict, conflict inspires human strength, heroism and will, while “the end of history” means being a well-behaved pedestrian on the road blazed by those who came before him, according to the traffic rules set by others. “History” means the tragedy of pioneering, and “the end of history” means the boredom of farming. The Germans who called for war before World War I, the France students in 1968, or even the youth in Western countries today who are forever “protesting”, under their superficial concrete demands, they may fundamentally express resentment at missing the “train of history” and the desire to gallop through the “historical” wilderness. For them, “recognition” means not only rights, but also the power to establish rights. This kind of history-making hero complex may end the “end of history” and make it “start all over again”.

And the characteristics of liberal democracy provide the soil for the fermentation and release of this “nameless discontent”. Openness is the greatest strength of liberal democracy, but it is also openness that makes it hostile. Quoting Revell, Fukuyama said: “A society characterized by continuous criticism is the only one that is fit for life, but it is also the most vulnerable.” “Freedom breeds suspicion, democracy breeds resistance, and when suspicion and resistance accumulate to a certain extent, liberal democracy can be destroyed, and it is not the competition of other ideologies or institutions that destroys it, but precisely the great achievements of liberal democracy. In other words, liberal democracy will decline from its own success.

Or maybe the concern is too pessimistic. On the one hand, at least so far, the vast majority of people’s desire to achieve heroism finds a way to be unleashed in different fields – you may not be Genghis Khan or Lenin, but as mentioned earlier, you can still be Steve Jobs, Jordan or Hemingway. Whether it is business, art, culture, sports or even politics, it is impossible to become a creator, a hero, and a “monument to history”. On the other hand, and more importantly, from the perspective of the past two hundred years or so, Bourgeois’s periodic self-loathing, no matter how stormy it may be, seems to have finally returned to and even strengthened the trajectory of liberal democracy. To a certain extent, this periodic self-loathing can be said to be a valve mechanism that helps to achieve the stability of liberal democracies by releasing the people’s excess political passions through circulation. In other words, even if this “nameless grievance” can temporarily interrupt the “end of history”, it will not bring history back to square one, but only make it stumble and then restore the balance.

Over the past two decades, “The End of History and the Last Man” has undergone all kinds of doubts. Yet, in the face of so much skepticism, twenty years later, the book remains unobsolete, still highly relevant to the world today – one might even say, highly avant-garde and forward-looking. This may be because, in terms of its awareness of the question – whether the idea of liberal democracy represents some kind of culmination of human political civilization – twenty years is too small a time scale to answer, and even more than two hundred years since the France/United States revolution are not enough to produce a definite answer. Of course, we can express our bewilderment: if, as Fukuyama or Kojève’s Hegel put it, “the end of history” does not mean the end of the conflict, then in what sense is this “end” itself meaningful and even cheering? Is history over, or has it changed its starting point and started the journey of “Season 2”? Such a question may only be answered slowly by time. All we can learn from the fate of this book is intellectual humility. If it is arrogant to think of a political system that originated in the West as “the end of history”, how is it not another to sneer at such a great expedition in political practice?